Dear All, Let Me Tell You About My Science!

Published:

One can speculate that, much like the learning curve, there is a curve of interest, starting with a vague acquaitance with whatever caught your attention, and then the universe starts to throw more things about ‘that interest’ in your way. At least that’s what happened to me after watching the last week of Kristin Sainani’s amazing Writing in the Sciences course, in which we were given an introduction and hands on dive into the Science Communication. Here in this post, I mostly wanted to put together bits and pieces that accumulated over time since my interest to this topic has started.

Communication purgatory

As I was learning to communicate in scientific language during my graduate student years, I had been also, intrisincly and inaware, carrying it to my daily conservations. Although communication with colleagues had been comfortable enough, advancing in this particular language wasn’t immeaditely bridging the gap of understanding when I wanted to tune into multi-disciplinary talks. Over time I’ve come to realize that some of these scientific talks are designed to address an audience that is almost as familiar with the topic as the speaker. Thus, the rest, who is intrigued by the title but has no idea about the domain, is left to their own devices to navigate through the domain-specific jargon. This is one side of the equation.

The other side involves public, people who are not familiar with our research and certainly not enthusiactic to hear the tiny little details we obsess over for months. But at the same time, they might love to hear about the consequences of this research (such as the impact of the advances in the field might have on their lives in the next few years) - which in turn means pruning nerd-y bits to bare minumum.

In summary, as researchers, on one hand, we are in constant need to dig deeper in order to keep up with the ever-growing domain-specific knowledge and on the other hand, we should be ready to be conceise and simple in our communication to be understood. And this dilemma is putting us somewhere I’d like to call communication purgatory. Science communication addresses both sides of the equation: the communication within scientists and the communication with public.

Painting your own sunset

Credit: jkq_foto

Earlier this year, the opportunity to gain more insight on science communication presented itself in DKFZ Career Day where I was able to attend a science communication workshop by Dr. Kristina Popova. She started the workshop by assigning us a simple task: drawing a sunset. Once the sunsets were ready, we deducted one point for each streotype item we had in our drawing: M shaped birds, horizon line, ocean, waves.. And then we were assigned to draw another sunset, one that we saw recently, a much realistic one, e.g. including apartments, tram lines, or a magnolia tree. Our drawings, simple as they were, became much more interesting than our almost industrialized first attempts. This was our first take-home message on how to communicate in science; by telling our own story.

However, as the audience may differ in background and interests, to try and deliver a one-story-for-all would not work at all. Dr. Popova addressed this with a formula of delivering the perfect presentation, also known as modes of persuasion:

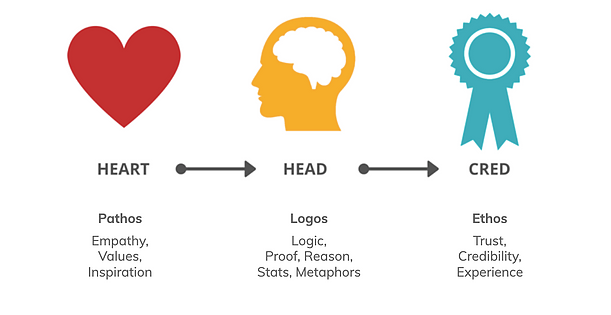

f(presentation) = a (ethos) + b (logos) + c (pathos).

Ethos, logos and pathos are the three main components of our storytelling where a, b, and c indicate how much weight we will put into the corresponding component. Ethos represents the credibility of the story teller, in other words, the level of expertise they assert on the topic (e.g. published papers, collaboration with other experts of the field etc.). Logos is the part that appeals to the brain where the story teller provides the data and statistics to convince the audience. Finally, pathos represents the part where the story becomes more personal and the story teller steps into the spotlight (e.g. motivation/inspiration to work on this particular field).

Credit: Growth Companion

The profile of the audience determines the weights one should put each of these three components. For instance, if we are to present in front of middle school kids, giving pathos more weight than logos might be good choice to engage them into the topic. On the other hand, if we are to talk to a group of researchers from another field, logos and ethos components dominates the conservation. Although, most of us intrisicly follow similar approaches in our communication with difference audiences, I found this simple function with few number of parameters very appealing and easy to remember. With that, I conclude this already long post with some reading suggestions from Science Communication experts if you want to dig more into the topic:

Am I Making Myself Clear? Secrets of the World’s Greatest Communicators by Terry Felber

Connection: Hollywood Storytelling Meets Critical Thinking by Olson, Barton, Palermo

Escape from the Ivory Tower: A Guide to Making Your Science Matter by Nancy Baron

I should also mention this very engaging talk by Jonathan Talbott on storytelling and collection of blog posts on giving better talks in general. Finally kudos to those of you who are patient enough to make it until the end and cheers to telling happy stories!